Setting Annual Goals

The most surefire way to disrupt organizational flow dynamics, send everyone to the bottom rung of the trust ladder, and discourage accountability is through poorly designed and executed annual goal setting.

Indeed, one of the most common unintended signals of disrespect that a manager can send to their team members is to spend time going through the motions of goal setting, only to stuff those goals into desk drawers and then pull the team in a different direction. “What’s the point?” is a common refrain when goal-setting season begins. “Nobody pays attention to them anyway.”

I put emphasis on the word unintended in the previous paragraph because many managers consciously understand the benefits of goal setting, but then undermine those efforts by allowing “shiny balls” to distract the efforts of the team.

Trust builds when actions are aligned with words. Flow is maximized when work is aligned up, down, and across the organization. Accountability flourishes in an environment of strong communication and multidirectional transparency. The three are inextricably linked, and strong goal-setting practices serve as the foundation for establishing trust, accountability, and flow.

Looking Through the Lens of Change Management

To punch the point, let’s look at goal setting through the lens of change management. You’ll recall from my recent muse that everyone has a unique set of change management curves. As a brief aside, note that I said “curves” and not “curve.” We don’t walk around with a singular change management curve that applies to all situations. While most of my personal change management curves have a similar shape, I will likely respond differently to the death of a family member as compared to a disruption to the team dynamic at work, or compared to the curve I navigate through when my local grocer moves the cheese from one part of the store to the other. “Who did move my cheese anyway?” I couldn’t resist the pun…

Let’s pause to think about what we just said for a moment as it clearly illustrates the complexity of the human experience and team dynamics. Everyone on your team has a different set of change management curves and each individual on the team has myriad situational change management curves whose shape depends on the circumstances of a particular event.

Hopefully you just had a huge “ah ha” moment as I did when I started learning about change. The “ah ha” is that management is much less about managing the technical aspects of workflow and more about navigating the vast complexity of helping fellow humans work with balance and harmony to achieve shared goals. Accidental managers like me are particularly prone to falling into the trap of believing that management is simply an extension of the technical aspects of the job they were so good at prior to being tapped on the shoulder to manage a team. “If we get the technical aspects correct, everything else will follow, right?” Wrong–management is all about striking the appropriate balance between the technical and behavioral aspects of the work. If you feel the need to lean one way or the other, lean into the behavioral, because if we get the behavioral aspects of our work environment correct, technical workflow becomes much easier.

Unfortunately, the clay layer (a.k.a. permafrost) of middle management likely became members of the clay layer through years of less-than-positive experiences with goal setting. The misalignment between actions and words, coupled with weak accountability frameworks, has left them jaded to the benefits of putting significant effort into developing and maintaining well groomed goals that are aligned up, down, and across the organization. Historical conflicts and communication challenges with the manager of the dreaded “Department X” definitely makes organizational soil less fertile and pliable. “Trevor never shares his team goals with me, why should I reciprocate?” And the wheel keeps spinning…

The point is this. Don’t expect instantaneous results from the installation of your management operating system–especially as it relates to goal setting. The clay layer will need time to soften, the permafrost needs time to thaw, and it will take multiple cycles in which words and actions align for team members to trust that all the hard work of goal setting won’t be tossed in the air like a salad when the next shiny ball bounces through the boardroom.

Setting Annual Goals

Enough with the rationale–let’s get on with the doing.

In my forthcoming book, we are building a framework of the necessary components of your business’s operating system so that components that are bespoke to your business operate with efficiency and harmony. To state the obvious, goal setting is one of those necessary components.

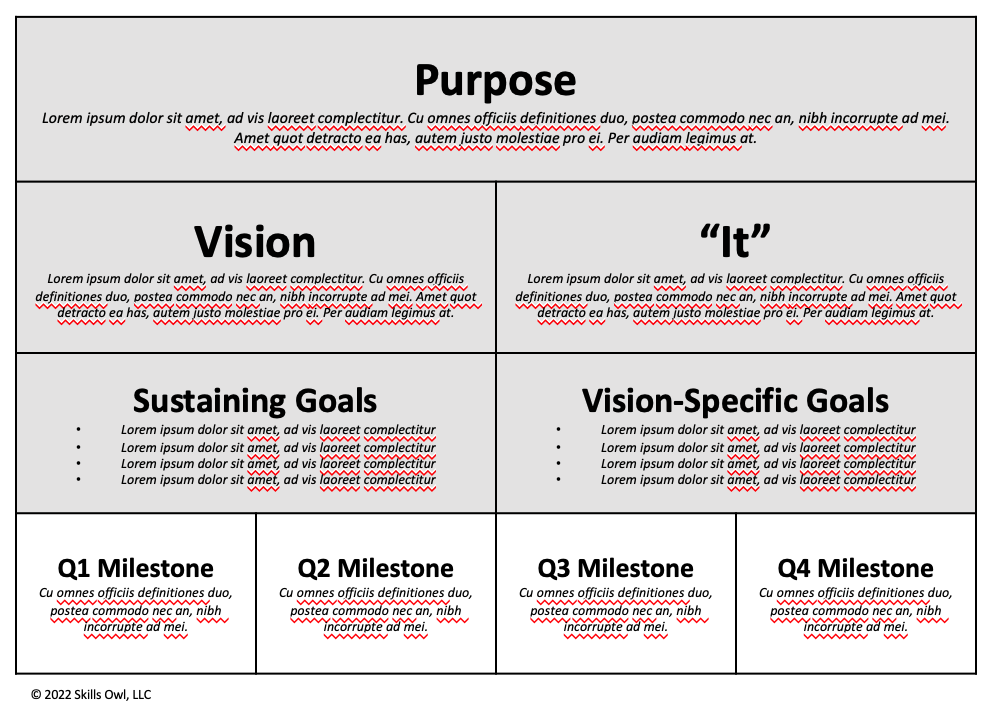

In my muse from April 16, 2022, we took a deep dive into the creation of the company’s master goal statements. Purpose led the way and our vision and “It” statements followed close behind. The rationale for this is to keep the organization’s purpose, vision, and what we do (the “It”) front and center throughout the year. It should be no surprise that annual goals are hung elegantly off of master goals to ensure that they’re woven into the flow of our work. As a reminder, here’s the master goal setting graphic from the April 16 muse.

Figure 1: Master Goal Template

Step 1: Setting Annual Milestone Goals

The good news is that the master goals exercise takes us a long way toward the completion of annual company-wide goals. Purpose, vision, and the “It” are established, as are sustaining goals and the intermediate-term vision-specific goals. The only thing to add are annual milestone goals.

Annual milestone goals represent “what’s most important” in the current period to drive forward momentum in either specific sustaining goals or vision-specific goals. Annual milestone goals are:

High level, but specific. In Figure 2 below, annual milestone goals are broken down by quarter, so the goal must be realistically achievable during that time frame. Depending on the structure of the business, milestone goals could be specific to H1 and H2 (first half and second half respectively) or even broken into thirds, or trimesters.

Applicable to the entire business. Although there may be cases where an annual milestone goal is specific to a functional area of the business (e.g., technology or sales), they should be crafted in such a way that team members in every functional area can see how their work will influence the achievement of the milestone.

Established early in the budgetary cycle. Nothing compacts the clay layer more than having company master goals handed to them late in the budgetary cycle. If master goals show up late or are ill-defined, a tremendous amount of waste is generated through over-processing and defects created by reworking individual budget components. Playing catchball between the senior executive team and the extended leadership team during the creation of milestone goals will reduce the likelihood of surprises.

Achievable. If I had to pick one of the five foundational elements of a well-crafted goal under the S.M.A.R.T. framework, it would be to stress the “A” in the acronym–achievable. Nothing crushes organizational morale more than consistently pushing dates farther into the future. Having personally gone through several decades of organizational goal setting exercises, I am NOT a fan of what are referred to as “stretch” goals. Your teams are already stressed and running at or near capacity. Imagining that a team has 110% to give is a false narrative and should be avoided to improve morale.

Understandable: Be deliberate with language throughout the goal-setting process. This is a miss in the S.M.A.R.T. framework. So much waste is generated by internal bickering over what a goal is meant to convey. Clarity and parsimony are essential. Avoid flowery or confusing language at all costs.

Figure 2: Annual Milestone Goals

Step 2: Setting Functional Area Goals

In many organizations, none of the “doing” happens at the senior executive level. Instead, each senior executive–with the exception of the CEO and possibly a specialty position–leads a functional area of the business with responsibility for execution of the plan and achievement of strategic objectives. Hence, functional area goals set the tone for the work that will be accomplished to support the master goals and company milestones. Functional area goals are defined as “what’s most important” to a specific part of the organization such as sales, marketing, technology, finance, or legal. Functional area goals are:

Supportive of company-wide Sustaining, Vision, and Milestone Goals. This may seem like a no brainer, but I’ve seen significant disconnects occur throughout my career between functional area goals and master goals. The underlying symptom of this misalignment is nearly always caused by a functional area leader who nods in agreement to the master goals with their colleagues in the board room but then decides that something else is more important for the success of their department. Dysfunction within the senior leadership team often has disastrous consequences downstream.

Established before the number-crunching starts. I’ve seen tremendous waste generated by overzealous, numbers-focused finance teams and leaders who jump right to building spreadsheets prior to the completion of functional area goals. When this happens, an artificial revenue, expense, or operating margin target becomes the focal point. At that point, goal setting moves from an organic exercise based on sound strategy to a futile effort to bend and twist goals to meet an unachievable number that’s not grounded in sound logic.

Developed using catchball. Just like the catchball exercise that occurs when setting master goals between the senior leadership team and the extended leadership team, functional area goals should be “tossed” to team leaders within the functional area (or a select group of individual contributors within the functional area in smaller organizations). This simple feedback exercise ensures buy-in, and minimizes unintended surprises–both of which will improve functional area trust.

Cross-walked against other functional areas. This is the place where most organizations fail in their goal-setting activities. Here, functional area leaders play a version of catchball amongst themselves, sharing and comparing their team’s plans to ensure consistency and understanding of handoffs and resource demands. Unfortunately, egos and historical tensions stand in the way of collaboration amongst senior leadership team members. So much waste gets generated when one hand doesn’t know what the other is really up to. Sure, high level goals might be shared, but oftentimes, fear of sharing dirty laundry or unearthing skeletons prevents the kind of transparency that’s necessary to create true organizational flow.

Aligned with incentives. Speaking of flow, nothing inhibits flow like misaligned incentive plans. If the master goal set says “expand product offerings through innovation” but the management incentive plan (MIP) says “grow operating profit by 10%,” which one of these potentially competing statements will win out? It will undoubtedly be the expense control necessary to achieve 10% operating profit growth, which will choke off spending necessary for innovation and the launch of new product offerings.

S.M.A.R.T.(er) than master goals. While master goals will, by definition, be more high level and aspirational, functional area goals must add an additional level of clarity to bring company master goals to life. This feature of goal setting carries through the process as we move from master goals to individual contributor goals. Goals get S.M.A.R.T.(er) as you get closer to where the work actually happens.

Figure 3: Functional Area Goals

Step 3: Creating Team Goals

In large organizations, it may be necessary to create team-specific goals. This may not be true of all functional areas of the business, but some functional areas may be large enough to warrant their creation. Before automatically assuming that team goals are a necessity, think first about flattening the company’s organizational structure. Individual team goals may inadvertently create waste and impede flow if their creation is not targeted to the teams that actually need them. Spreading policies like peanut butter can create unnecessary waste in motion and over-processing.

An Aside–Why Individual Goal Setting is Hard

The creation of individual goals is where the rubber meets the road and where goal setting ultimately succeeds or fails. From my experience, goal-setting breaks down at the individual contributor level because the process moves from a strategic planning and budgetary exercise to a human resources or talent management exercise. This is where well-intended human resources information systems (HRIS) and the desire to get goals into the “system” runs headlong into well-crafted goals and organizational flow.

In fact, goal setting at the individual level ends up being combined with the annual performance review process in many organizations, bringing the elegant cascade from master goals to functional area goals to individual goals to a screeching halt. This is because individual goal setting is part of the company’s “talent management season” and master and functional area goals are part of the company’s “budgetary season.”

Hence, at the individual level, goal setting becomes an annual “check the box” talent management exercise that everyone ends up loathing. That is because corporate HRIS systems become bloated over time as one-stop employee and company information shops. They’re like air traffic control systems that take so long to build and customize that once they’re in place, they’re obsolete. Pause for a moment and think about your company’s HRIS system. It likely contains compliance, pay, benefits, goals, performance evaluations, competencies, team hierarchies, and a host of other employee and company information.

Moreover, HRIS systems are typically not the primary piece of software that individual contributors use day in, day out. Yes, employees will routinely access the software for pay and benefits information, but other parts of the software package may be used infrequently, forcing the employee to effectively relearn how to use it when talent management season rolls around. Goals and goal setting fit squarely into this category. “What are my goals again? Oh wait, let me log into the HRIS system, fumble around to find where my goals are buried, and I’ll get right back to you.” It’s no wonder that there’s a divide between the creation of company master goals, functional area goals, and the individual goals that should be guiding day-to-day activities.

Step 4: Creating Individual Goals

Our aside on the challenges with HRIS systems–and the clunky handoff of goal setting between budget season and talent management season–illustrates clearly why most goals get hidden away or locked into digital desk drawers, only to see the light of day during annual performance reviews.

In a perfect world, individual goals are part of ongoing performance coaching conversations between managers and individual contributors throughout the year. If goals must be contained within the company’s HRIS system, then both employee and manager must be properly trained on its use. While this may come as a surprise to some, many managers–especially accidental managers–are not experts in the operation of the company HRIS system, and go through a similar reeducation process each year during talent management season.

Hence, individual goals should be:

Visible. Print your goals on an actual piece of paper and pin them up in your regular workspace. They should be right in front of you as a constant reminder of what’s important to help minimize distractions and prevent the inevitable pull toward shiny balls.

Tied directly to coaching conversations. Good managers engage in routine coaching conversations with their direct reports and don’t wait to pile all their feedback into an annual performance review. Engaged employees welcome constructive coaching and feedback as the gift it is. At a minimum, goals should be discussed on a quarterly basis between managers and direct reports–preferably monthly. These conversations should focus on progress to date and any midstream changes that need to be made to maximize alignment.

Tied to the Gemba. We’re going to talk in detail about the gemba walks and gemba boards in future muses. For now, all you need to know is that “gemba” is Japanese for “site” or “scene.” In continuous improvement parlance, the gemba is where the work occurs. Personal goals should be tied as closely to the work as possible–this applies to technical goals (e.g., get x done by y date) as well as human development goals (e.g., acquire new skill z). Gemba walks are typically done at the department level, so tying individual goals to the gemba effectively means that there is a strong linkage between individual and departmental or functional area goals. To maximize flow, tie goals to the gemba.

Aligned with incentives. Keep a keen eye out for misalignment between goals and incentive packages. If individual goals say one thing, but incentives are aligned with something else, a collision will occur–whatever work is most closely related to monetary or non-monetary incentives almost always wins.

S.M.A.R.T.(est). Individual goals are the most granular in the company and the S.M.A.R.T. framework should be applied rigorously.

Specific: The language used to craft a goal should be carefully chosen to minimize confusion and the potential for misinterpretation. Since goals are often tied to formal performance evaluations, it is in everyone’s best interest to strive for clarity.

Measurable: This is a tricky one. The old saying that’s often attributed to Peter Druker says “what gets measured gets managed,” but this reference has been debunked and strict adherence to this concept can lead to unintended consequences when measurement is forced. Therefore, the manager and individual contributor should think carefully about what “successful completion” means and how success will be measured. Use the “five whys” to explore potential root causes of measurement challenges and to determine the best way to measure success.

Achievable: As we’ve discussed before, nothing saps morale more than installing goals that are likely to be unattainable. I’ve personally woken up on a New Year’s Day (or five) with a set of stretch goals that I knew were already under water. Needless to say, those were extremely difficult years. Engagement rises when goals are achievable.

Realistic: This item is closely related to achievability. Are all the resources and support systems in place to ensure the achievement of a goal? Have all dependencies been considered? If team one must deliver x before you can even get started working on your goal, and/or team one is known to be unreliable, then don’t commit without cross-walking your goal against the goals and resourcing of team one.

Time Bound: Open-ended goals are also morale siphons. Make sure there’s agreement on when a project or outcome is to be delivered and ensure there’s going to be adequate resources available for completion.

Conclusion

Effective goal setting can serve to promote organizational flow when there is alignment and consistency of goals up, down, and across the business. Weaving goal setting into the flow of business operations also prevents episodic lurching and waste that’s generated when everyone must stop what they’re doing to create goals that aren’t discussed or reviewed on a regular basis.

Goal setting also has the positive knock on effect of honing communication and storytelling skills. It’s one thing to create a set of goals. To truly get value from the process, it’s essential to be able to communicate the story that’s encapsulated within a set of goals. Don’t make the erroneous assumption that the act of codifying goals represents the end of the process. Continuous communication and reinforcement across myriad stakeholders is essential in order to bring goals to life.